From April 1st the tax ring-fence for rental property losses needs to be accounted for by investors. It is currently going through the ‘bill to law’ process, which starts with a Select Committee and then ends up before Parliament for the final stage.

In other words, although it’s not law just yet, it looks pretty likely to pass and once approved will apply to the current tax year (ending March 31st, 2020).

After a lot of discussions and a long build-up, it means that mortgaged landlords will no longer be able to use a loss on a rental property to reduce the tax bill on their non-property income(s). There’s been much teeth-gnashing about the potential effect and certainly some individual landlords will have to look at their sums.

As it happens, Australia is paying similar attention to their negative gearing regime, with much of the commentary there focusing on how it’s only utilised because of the concurrent existence of big capital gains. Without those gains, reliance on negative gearing looks less appealing.

But back to New Zealand, I’m relatively relaxed about the potential for mortgaged investors to sell-off (and/or new investors to stop buying) because of the tax ring-fence on rental property losses. There are two factors here:

Because of the LVR rules, investors have already required a deposit of at least 30% for the past few years and will, therefore, be more likely to be making operating profits than in the past – hence, less likely to be utilising the tax advantage of a loss.

It’s a ring-fence, not a complete removal. Mortgaged investors can still use a loss on a particular property to reduce their overall tax across a portfolio of properties or on a future gain on the same property.

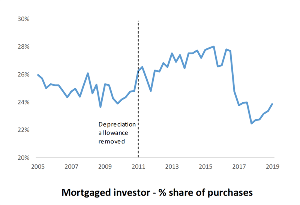

Another reason for reassurance is that the removal of the depreciation allowance in April 2011 (which, similar to the ring-fence, changed the tax economics of property investment) didn’t have a clear or lasting impact on investor behaviour.

On our Buyer Classification series (shown in the chart on the right) the share of purchases going to mortgaged multiple property owners (MPOs) did lift from 25% in Q4 2010 to 27% in Q2 2011, then dipped back to 25% by Q4 2011 – which could have been volatility related to the tax rule changes.

But any impact certainly didn’t last; the market share for mortgaged MPOs generally trended higher for the next 4-5 years.

(We’ve ignored cash MPOs here, because they’re much less likely to running properties on an operating loss or, in other words, won’t be using the tax advantage of negative gearing.)

Admittedly, around that time (2011), property price rises were starting to kick into gear and these gains may have masked the effect of removing the depreciation allowance. This scenario doesn’t apply now, and in Auckland property values have even started to drop a little.

That could theoretically produce a more noticeable effect from the ring-fence. Indeed, it’s clear that any changes to tax laws will impact individual landlords to differing degrees and the new ring-fence may be too much for some to bear.

But let’s not forget that other landlords may see that as a buying opportunity and, on the whole, I doubt that the supply of rental property will be reduced by the new law.

It may well just mean that to make their required/target profit, landlords now just choose to extend their holding period (either in absolute terms or relative to other buyer groups) – that’s certainly something we’ve seen in our data lately.

Ultimately, I do not expect a sea-change in investor behaviour as a result of the tax ring-fence.

*Kelvin Davidson’s article was originally written as a guest blog for the Auckland Property Investors Association. It is reproduced here with his permission.