By Simon Angelo - Wealth Morning

In Auckland, home prices are down nearly 22%. More than in almost any other global city.

How did this happen? And what will happen next?

Let’s start from the beginning…

The typical mum and dad investor in New Zealand builds up some wealth, then buys a rental property or two. I’ve met many of them. They’re planning for their retirement. A good thing to do.

Today, the rental property sector is a bigger asset class by GDP than in other developed countries.

There have been years of overfishing in that small pool. It’s now rare to find a residential investment that delivers any decent actual net yield.

By actual net yield, I mean the return from rent after all the costs and time involved.

So, by definition, these investors depend on healthy capital gains. Which, to be fair, we have seen over the past decade.

Yet, there are no certainties when it comes to investing for the future. Only probabilities.

I see headwinds coming from two directions. With the probability of being financially hazardous.

1. High property prices (by measure of median-income) are still unsustainable

These prices depend on historically low interest rates for the most part. High rates of net migration. And restrictive building/zoning.

When interest rates rise rapidly — as we’ve seen following Covid’s monetary overshoot — the rug gets pulled from under home prices.

As we track toward variable mortgage rates of 10%, values could crumble further.

There is also the risk of economic shock or trauma. About 12.5% of the adult population already has debt in arrears. Debt they cannot afford.

Of course, when the cycle turns and interest rates start coming down, this could see values grow again.

Which puts us in the firing line of another, wider headwind risk…

2. Political pressure will keep coming for the ticking time bomb of unaffordable housing

The cost of housing has often ranked as the country’s biggest election issue.

There was pervasive anger when first-home buyers found themselves losing out at auctions to investors, only then to see the same home listed for an astronomical rent shortly after.

Labour’s first drastic solution was to deny investors the ability to deduct mortgage interest. Along with an extension to the Brightline ‘capital gains’ test.

National, not known for much drastic action, then teamed up with Labour to force medium-density standards across all the major cities.

Some very blunt legislation that does enable supply — but in the process threatens to kill off the Kiwi way of life with bunker blocks.

The ACT Party was the only party in parliament to oppose this, instead proposing other solutions to incentivise building, infrastructure, and drive supply.

Alongside National, it has also campaigned to restore interest deductibility for investors.

But this doesn’t yet resolve the political issue of many younger Kiwis still priced out of the housing market. People who feel a sense of hopelessness because they may never own a home in New Zealand.

We need to recognise housing as a necessity. As shelter. A vital — yet once built — unproductive asset class. We also need to see home ownership as an investment in society. A public good.

If one owner of that asset class — investors — can deduct mortgage interest, then all owners with a mortgage ought to be able to do so. (This was the case when I lived in Europe).

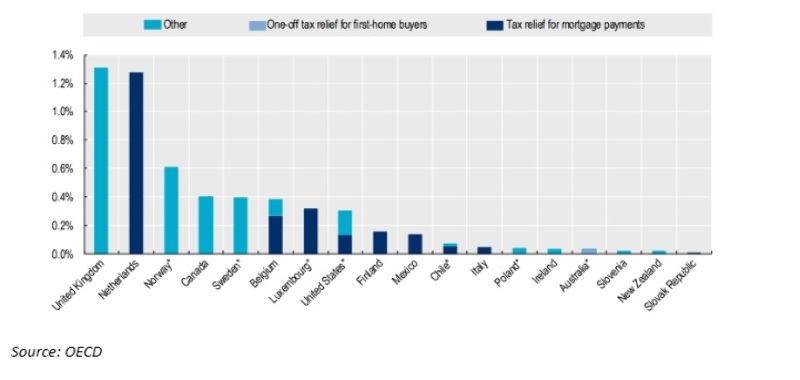

In many other jurisdictions, mortgage on interest for rental properties is treated differently:

- in the UK, landlords cannot deduct mortgage interest but can receive a tax credit based on 20% of that interest bill;

- in the US, all home owners may qualify for a mortgage tax deduction on up to $750,000 of borrowings. In fact, the Home Mortgage Interest Deduction (HMID) is one of America’s most cherished tax breaks — incentivising home ownership;

- in Italy, a 19% tax deduction on mortgage interest is available to all home owners, subject to certain limits;

- in Denmark, interest on mortgages is deductible for all home owners; and

- in Switzerland, mortgages for home owners are fully tax deductible.

In New Zealand, the situation before was no tax incentive for home ownership. Only for landlords, who thus gained a competitive advantage.

In fact, the country had among the lowest tax support for owner occupiers in the OECD:

Tax deductions should be used to incentivise desirable activity. In particular, home ownership across society.

We have now moved the incentive dial toward building more housing. New build rentals can still deduct mortgage interest. This makes sense. Not the misaligned incentive for investment into existing and constrained housing stock.

Now, those with mortgaged rental properties will likely be up in arms at this point.

Yes, you’ve worked hard to provide warm and dry housing someone may rent. But, often, you are also renting out a home that could have been bought by an owner-occupier.

And, no, your rental property is unlikely to be a viable business. A study on the sector showed the average rental property returning around 0.3%. But this was before most moved off interest deductibility and rates were lower. Meaning, today, most are probably loss making. Any profits depend on speculative capital growth.

If you put many rental properties against listed businesses, they would be uninvestable by return on equity alone.

National and ACT were tracking to win this year’s election.

Yet if they fail to get the housing crisis under control, the stage is set for more drastic opposition from the other side.

Property in New Zealand doesn’t always go up. It’s not a one-way bet. But it is the Kiwi dream that every New Zealander can one day own their home.

Some say the New Zealand economy has been failing to deliver for too many people for too long.

Unaffordable housing, wages not keeping pace, unsustainable household debt, and surging division are all signs of that.