By Greg Smith, Head of Retail at Devon Funds

September has been a tricky month for markets so far, with investors intently focussed on the tightening plans of the Fed and other central banks around the world, as many officials double down on efforts to contain inflation. At the same time economies have remained resilient, as have corporate earnings in many instances. This has certainly been the case in New Zealand with June quarter GDP coming in ahead of expectations by some distance, and the reporting season a solid one. This, and further weakness in our currency (which is positive for our exporters), has arguably helped the New Zealand stock market hold up better than many international peers.

In what has been a volatile month so far, the NZX50 is down around 1.5%. In comparison the S&P500 has fallen 5%, while the Nasdaq is nearly 6% lower as higher-priced growth stocks have fallen further out of favour amid concern over rising interest rates. Across the Tasman, the ASX200 is down almost 6% so far this month.

Globally, investors have been concerned around the view that interest rates will be ‘higher for longer.’ A hotter than expected inflation print in the US has provided the catalyst for recent volatility. The annual rate of inflation was lower at 8.3% but ahead of forecasts of 8% and “core” inflation accelerated for the first time in six months. This cemented the prospect of a ‘jumbo’ rate hike which was duly delivered when the Fed met.

The US central bank put through a third consecutive 0.75% increase in rates which was widely anticipated and less than the 1% rise that was also on the cards. This takes the central bank’s main interest rate to a range of 3-3.25%. It was the outlook that was always going to be under scrutiny, and the picture painted is one where the Fed is far from done in the current tightening phase. The “dot plot” of individual officials’ predictions pointed to further large increases and no rate cuts before the end of next year.

The Fed now expects the terminal rate (where it ends its tightening regime) to reach 4.6% in 2023. This implies another 0.75% hike (which would be the fourth in a row) when the Fed meets next in November. A key sentence from Jerome Powell was that “Higher interest rates, slower growth and a softening labour market are all painful for the public that we serve, but they’re not as painful as failing to restore price stability and having to come back and do it down the road again.”

Powell said his main message was that the central bank officials were “strongly resolved” to bring inflation down to the Fed’s 2% goal and added that “we will keep at it until the job is done.” The comments invoked comparisons with Paul Volcker, the Fed Chair whose aggressive tightening in the 1980’s ultimately brought on a deep recession.

Many like to bring up Volcker, with comparisons regularly made, but there are however some big differences. Over four decades ago, the US central bank was much slower to react to inflation in the 70’s which ultimately peaked at just under 15% in 1980 – it looks to have peaked at 9.1% in June. The central bank during that time took rates to 20% in 1981, and no one is really suggesting rates will get much above a quarter of that level. The scenario this time around is very different. The Fed is not behind the curve to the same extent.

The world’s largest economy is coming from a position of strength – a noted change from the Fed’s previous statement highlighted that recent indicators point to “modest growth in spending and production.” Officials have lifted their median unemployment forecast to 3.8% by the end of this year. It sees the jobless rate reaching 4.4% in 2023, where it will hold through 2024 before easing back to 4.3% in 2025. This is hardly an apocalyptic scenario.

For all the alarm bells, the US economy is not rolling over, despite the aggressive tightening seen already this year.

These recent comments have though seen a reaction from the bond market, with the yield on the 2-year Treasury jumping to 4.1% while that on the 10 year is now 3.7%, the highest level since 2011. US 30-year mortgage rates have risen to 6.29%, the highest level since 2008.

Where the Fed goes, other central banks often follow. This is all the more so currently given the strength in the US dollar has compounded the level of imported inflation for those countries where their currencies have weakened. The Swiss central bank has recently raised rates by 75bps and was the last country in Europe to take rates out of negative territory. At 3.5%, inflation is less of an issue than the likes of the UK (where it hit 9.9% in August). The Bank of England went with a lesser 50bps rate hike but has (significantly) reduced its peak inflation forecast to 11% in October, from 13% previously. This was the seventh consecutive hike and officials said that they were not on a “pre-set” path.

Across the Tasman though, the minutes of the last RBA meeting revealed that the board sees the case for a slower pace of rate increases “becoming stronger” as rates rise. Officials are though maintaining the view that “the size and timing of future interest rate increases will continue to be guided by the incoming data and the board’s assessment of the outlook for inflation and the labour market, including the risks to the outlook.” Are we starting to see signs that central banks are not that far away from pivoting back to a more neutral (or less hawkish stance)?

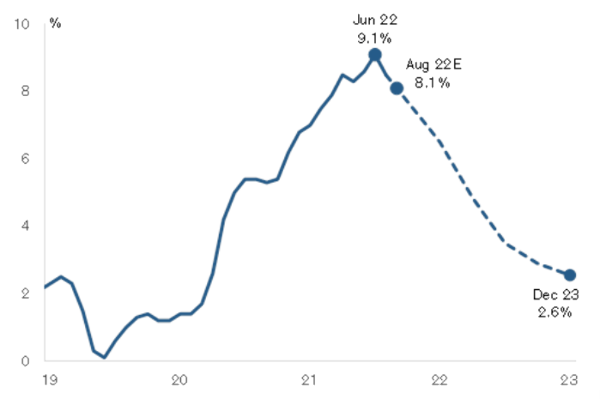

The hot US CPI print continues the pattern of ambiguity around data prints and incredible amounts of noise which markets continue to face. US producer prices declined in August. Annually, headline consumer inflation did actually fall, which does not undermine the view that top-line inflation has peaked. Oil prices are a key driver in this regard and have fallen 30% since their post-invasion peak earlier in the year. Mathematically it was always going to be hard for CPI prints to remain as strong as they have been. As shown below, forecasts for future inflation have fallen substantially.

Economists’ Forecasts for US CPI

Source: Credit-Suisse

Meanwhile, most economies are still in a good spot, and are coming from a position of strength. US retail sales rebounded unexpectedly in August, with a 0.3% gain on July. Forecasts had been for zero growth, and some areas of spending were notable. Consumers have more in their pockets thanks to the fall in petrol prices. This is a trend being seen elsewhere.

Job markets are also strong. US manufacturing has ticked higher recently, and continuing claims for unemployment remain near historically low levels. This all comes following what was a generally stronger than expected earnings season in the US.

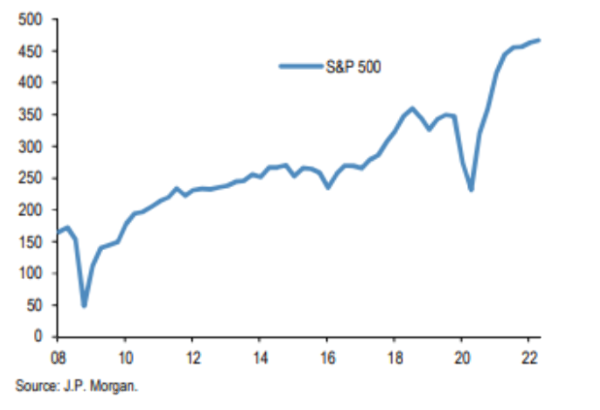

Quarterly Earnings of S&P500 companies

New Zealand of course avoided a technical recession in the June quarter, and by some distance. The economy expanded 1.7%, which was at the top end of forecasts. The services sector, which accounts for two thirds of the economy, played a key role by rising 2.7% quarter on quarter. Covid sensitive sectors bounced back. Many forecasters ultimately underestimated the extent to which the economy would bounce back following the Omicron-impacted first quarter.

The level of backslapping should however be tempered. Goods-producing industries fell 3.8% quarter on quarter, with manufacturing and construction under the pump. On an annual basis, economic activity was just 1% higher. Overall household spending declined (-3.2%) much more than expected, and there remain plenty of challenges to the outlook. People are paying less at the petrol pumps, but swathes will be seeing higher mortgage bills in the months ahead as they roll off one-year deals struck last year. This is while the number of million-dollar-plus mortgages has doubled in just three years to nearly 103,000, or nearly 9% of all borrowers.

Whether a soft or hard economic landing is forthcoming remains to be seen. The uncertainty here is however seeing good support for high quality, defensively positioned companies.

This year’s volatility has certainly had some wide-ranging impacts, not least of which being in the IPO market, which has ground to a halt. It has been 120 days since a US company raised at least US$25m in a traditional IPO. This breaks the longest previous drought which was seen in 2008. The drought has been even worse for the high-priced technology sector.

It has been over 240 days since the bell was last rung at the Nasdaq on a tech IPO worth more than US$50m. This surpasses previous stretches seen in the aftermath of the GFC, and also the 2000s dotcom crash. A near 30% cratering in the Nasdaq this year, and the implications for pricing and investor demand, has left corporates somewhat gun-shy. The performance of pandemic IPOs has also made investors wary. The Renaissance IPO index, which tracks US companies that listed in the past two years, is down nearly 50%.

At least Europe does have a big IPO on its way, and indeed one which will be the largest in a decade. Volkswagen has confirmed it is aiming for a valuation of €70-€75 billion for Porsche AG. The European IPO market has largely been shut this year, with IPO funds raised down 83% on the same period last year. Porsche will provide a welcome boost, with the near €10 billion being raised shaping up as the largest IPO since that of Glencore in 2011.

Overall, investor sentiment of late has not been helped by some bold projections from those on the bearish side of the ledger. Amongst those commanding the most attention has been billionaire hedge fund manager Ray Dalio who says that markets have become too complacent about inflation and underestimated how far interest rates will rise. The co-investment officer at Bridgewater expects inflation to fall in the short term but rise in the medium term to a sustained average level of around 4.5% to 5% (versus market implied forecasts of around 2.6%). He expects the Fed will continue to raise rates to at least 4.5%.

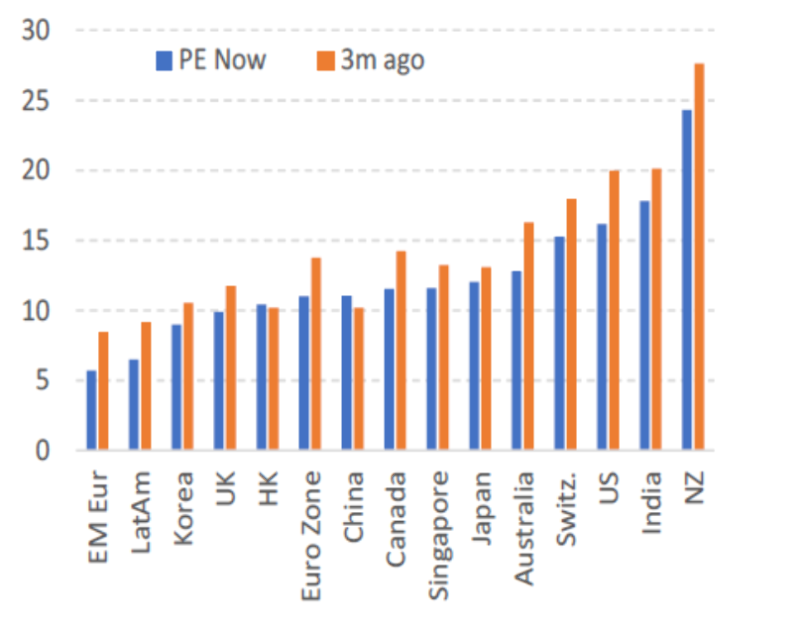

The alarm bells being rung by the bearish camp are nothing particularly new, and indeed make a market. It is worth noting however that a lot of bad news has already been priced into markets (see below for a comparison of market PEs vs three months ago), and while not apocalyptic scenarios, these are certainly less than favourable ones. This is showing up in valuations. Devon MD and Portfolio Manager Slade Robertson has noted that if one takes out the US mega-cap stocks, the valuation on the rest of the SP500 is around 13-14 times earnings.

Market PEs today vs three months ago

Source: MST

Earnings would contract further if the economy turns down, but it remains uncertain to what extent. Many economies are still characterised by strong employment markets and pent-up savings. Some areas of inflation are already cooling (although a strong US dollar has helped) without central bank intervention.

Whether economies will see a soft or hard landing remains very much up for debate. This is while, from a markets’ perspective, the short-side appears to have become increasingly crowded. The fact that markets are often on edge waiting for the words of one man (Jerome Powell) highlights the dilemma currently being faced. Arguably it there has never been a more important time for investors to have high quality companies in their portfolios. When the market does snap back, a rising tide might not lift all boats this time around, and indeed may separate the wheat from the chaff.

Comments

No comments yet.

Sign In to add your comment