By Greg Smith

This has given rise to some concerns over stock market valuations, which have been elevated, particularly in the technology sector. Central banks have been responding to the inflationary pressures resulting from (successful) stimulus initiatives administered during the pandemic. These inflationary pressures have of course intensified following Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine last month, which has sent prices for oil, nickel and wheat (amongst other commodities) soaring.

After an initial downward lurch following the onset of war, markets have stabilised. Investors appreciate that the world can find other channels for sourcing much of what Russia supplies, and for longer than Russia can probably stay solvent. The pressing need for interest rate tightening however has not gone away however, with inflation at multi-decade highs in New Zealand and in many other countries around the world.

The New Zealand central bank was a lone wolf in embarking on a tightening journey last October, but other central banks are following suit, led by the US. Recently Jerome Powell indicated that the Fed was ready to raise rates sharply if needed to counter inflation which he said was “much too high.”

Powell’s comments come less than a week after the Fed declared a lift-off on rates for the first time in three years. Ten-year US Treasury yields have since surged to around 2.4% after Powell indicated that the Fed could raise rates by more than 25 basis points at each meeting if necessary to contain inflation. The markets have been pricing in 25 basis point hikes at each of the six remaining FOMC meetings this year.

The reaction to the comments from the Fed Chair highlight the sensitivities around the rate tightening journey. This is new territory for investors after an era of ultra-low interest rates. But there is also cause to believe that the broader markets can acclimatise to the ascent in interest rates, even if the bar of expectation for higher priced stocks will become a more challenging one.

A tightening of rates following the trauma of the pandemic, and the stimulus administered as a result, is a vote of confidence in a rebounding economy. As noted last week, rate rises per se are also not necessarily something to be feared by equity investors, which we can see by looking back at the most recent previous tightening initiatives (2004-2006, 2015-2018) when equity markets performed strongly.

Inflation does need to be addressed, and efforts here have been complicated by the outbreak of the war.

Tech stocks have been at the epicentre of this year’s sell-off, with the Nasdaq Composite in correction territory (at one point down as much as 17% from the November high). The tech laden index made one of the worst starts to a year in half a century of its existence, on a par with the 10% decline in 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis. Volatility has continued, and the index has recovered somewhat but remains down around 9% year to date.

The prospect of rising interest rates has thrust the spotlight on the surge in the valuations of growth stocks that has occurred since the onset of the pandemic. Many high-priced tech names have as a result gone into reverse, with more than half of the Nasdaq constituents having at one point fallen 50% or more from their 52-week highs. This has also led to questions over whether ‘’growth’ has had its day, and a rotation towards ‘value’ style investing may be the story going forward.

The term ‘value investing’ is a widely used one, equally one that is often misunderstood. Many investors will know that ‘officially’ the concept was originally developed by Columbia Business School professors Benjamin Graham and the lessor known David Dodd in 1934. It was later popularised in Graham’s 1949 book ‘The Intelligent Investor’ (well worth a read if you get the chance).

Effectively a value investing strategy involves identifying companies which are trading below their intrinsic value (often determined as a range), which is modelled through the analysis of quantitative inputs (balance sheets, profit & loss etc). Qualitative inputs (such as, but not limited to, the company’s brand, business model, competitive positioning, management) are also assessed as part of the investment process.

Warren Buffett is of course one of most well-known disciples and arguably the most consistently successful proponent of value investing thus far in history. Buffet in fact studied under and was mentored by Graham, and throughout his career has regularly been at pains to point out what a successful value-based investment strategy is.

One of Buffett’s best-known quotes is that “It’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price, than a fair company at a wonderful price.” This goes to the essence of the value investment ethos, which involves buying (high quality) stocks at a discount.

Growth investing meanwhile is a widely popular alternative to value investing, and in many ways is at the opposite end of the spectrum. This investing style effectively seeks out companies that exhibit above average market rates of earnings growth, and the assumption is made that they are likely to repeat this into the future.

Growth investors are typically willing to ‘pay up’ for such levels of growth and pay above market multiples across a variety of valuation metrics.

Investors following a growth style tend to take a helicopter view of a business’s free cash flows well into the future. The higher interest rates are, and the further the time out before cash flows are expected to be generated, the less each dollar of those future cash flows are worth.

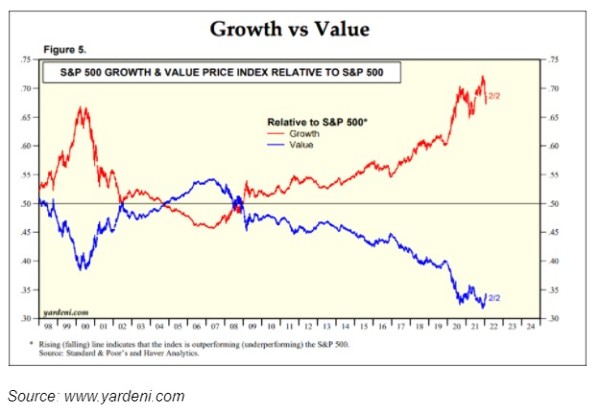

Given the above relationship it may not surprise that growth stocks have been highly sought after while interest rates have been ultra-low, particularly since the Flobal Financial Crisis. Substantial levels of stimulus were of course injected into the financial system during that crisis, and this has occurred again during the pandemic over the past two years. Central banks have maintained cash rates at or near zero, while also flooding the system with liquidity (e.g. quantitative easing) to keep bond rates low.

These stocks have also been in demand as many high growth sectors, led by technology, have had their earnings trajectories turbo charged by the pandemic, and the stay-at-home thematic. Many older economy/value style sectors (think financials, industrials, reopeners) have in contrast been hampered by Covid, and been less in favour as a result.

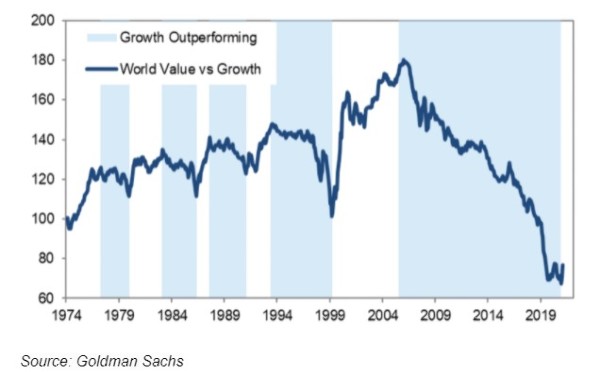

This and a low interest rate era have all served to extend the outperformance of growth vs value. As the chart below shows, this period of outperformance (shaded light blue) has endured longer than at any other points in the last 50-years.

The Great Rotation – why now?

There are a number of reasons in our view why the environment in the years ahead may be much more favourable for value investing as opposed to growth strategies. Indeed, there is a case that baton change may not only be fairly swift this year, but will endure for a very long time.

At its simplest, the reality is that the ultra-low interest rate environment is coming to an end. The question over whether the Fed and other central banks will raise interest rates, two, three, four, or five times this year is moot. The inflationary outcomes successfully delivered on the back of unprecedented global monetary and fiscal stimulus initiatives mean that central banks are now focussed on tightening measures here on in, effectively “taking away the punch bowl.” Interest rates are going higher, no question.

The pivot by central banks, led by the Fed in the US, away from the ‘transitory’ inflation argument late last year was significant. The RBNZ of course was one of the first to go early on rate hikes in October, but markets are now facing the reality that most central banks will be in tightening mode this year. Interest rates will be heading north.

As noted, higher interest rates have a disproportionately negative effect on the valuations of growth stocks, which depend on cash flows expected far into the future. A dollar earned in the future will be increasingly worth less than it is today. The bar of expectations will rise, and this may already be playing out in the recent US reporting season. As we also know, where the US heads the rest of the world tends to follow, and this may be the case with the rotation from growth to value in 2022.

While companies that hit the mark (such as Amazon) were rewarded, those which have delivered a negative surprise on their future earnings outlooks were punished, with Netflix, Tesla, and Spotify all high-profile examples. The most extreme was however the reaction to numbers from Meta Platforms. Facebook’s parent reported a 20% lift in quarterly revenues, but net income came in below forecasts as costs blew out. User additions have also stalled as younger generations are heading to rival platforms. The stock fell 25% on the day of the release, losing around US$250 billion in value, the biggest one day fall in US corporate history.

Does the reaction to outlook statements from these global tech growth names, which have boomed during the pandemic, mean that the day of reckoning has arrived for growth stocks? If so, this is especially concerning given the performance divergence between the two styles since the GFC has been the largest in history.

It is quite possible that investors are going to be increasingly cognisant of the high valuations that many growth names continue to trade on despite the recent correction, as the prospect of ongoing interest rate rises effectively raises the bar of expectations.

Such a global trend could be highly relevant to investors in the New Zealand and Australian markets. The rotation away from growth will to be the benefit of companies that fall into the ‘value camp.’ A report from Goldman Sachs recently showed that ‘low PE’ firms on the ASX200 trade at a 58% discount to the market, which is 13% below the 20-year average. The below chart also highlights that the “PE gap” between value and growth stocks across the Tasman has started to narrow slightly of late but (at -7.6x currently) has substantial scope to close further.

There is clearly substantial scope for a significant and sustained re-rating as this ‘value gap’ closes, but also as ‘expensive’ stocks fall further out of favour with global interest rates rising. It is worth noting that an inversion of the yield curve (the US 5-year has gone above the 30-year Treasury yield for the first time since 2016) suggests that the bond market is starting to price in recession. However, the world economy is still expected to grow strongly this year (in the region of 3%), despite substantial price shocks emanating from the war and as the world reopens post Covid.

The relative appeal of value stocks could therefore well gain in the ascendency. Many old economy stocks and sectors that are tied to the economic cycle could thrive in such an environment.

Against this backdrop, it may be wise for investors to seek out and maintain exposure to high quality companies with excellent investment credentials, including strong track records, robust balance sheets, great management, great economic moats and strong long-term earnings prospects. Ticking all these boxes and ensuring that the right price is paid for each business could well be essential to driving performance outcomes over the next stage of this cycle. As Warren Buffett also once said, “Price is what you pay, value is what you get.”

The Devon investment funds have navigated this year’s volatility with a very strong performance, highlighting the benefits of an active, value-driven investment style. Return figures from Morningstar to 28th March have all the Devon funds in the top industry quartile (for the funds covered by Morningstar) over a 3-month rolling period, and most within the top industry quartile over 6 and 12-month rolling periods. The Devon Dividend Yield Fund is ranked the top Australasian equity fund over a rolling 3-month period for the funds covered by Morningstar.

About Devon: Devon Funds Management is an independent investment management business that specialises in building investment portfolios for our clients. Devon was established in March 2010 following the acquisition of the asset management business of Goldman Sachs JBWere NZ Limited. Devon operates a value-oriented investment style, with a strong focus on responsible investing. Devon manages six retail funds covering across the universe of New Zealand and Australian, equities and has recently launched two new international strategies with a heavy ESG tilt.

For more information please visit www.devonfunds.co.nz

Comments

No comments yet.

Sign In to add your comment