Last year Wealth Morning interviewed CAP, a nationwide group dealing with debt and poverty –housing cost pressures were found to be the key cause of deprivation.

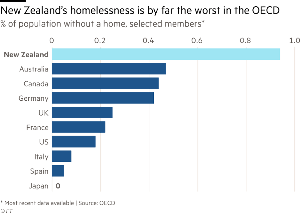

Many people after paying rent, and even mortgages, are left with barely anything to live on – while New Zealand’s homelessness is the worst in the OECD.

The stats

- Almost one in 100 New Zealanders are homeless.

- Home ownership in Auckland dropped to 59.4% of households in the 2018 census (it was 72.7% in 1991). This is likely to be even lower now.

- For the past five years, house prices have been rising much faster than wages – with Auckland’s median price in mid-2020 now 11.5x median income.

- Auckland is now more “unaffordable” than San Francisco or London. And every urban housing market in New Zealand is “severely unaffordable”, according to the 2020 Demographia Housing Affordability Survey.

- A debt time bomb is in the making, particularly for the young. Mortgage brokers tell us they routinely see debt-to-income ratios of 6x or more. The legal maximum for most home lending in the United Kingdom is 4.5.

It is not only a housing issue. It is an investment issue, where capital is not channelled to economic activity, but to speculation on rental housing.

How did a progressive country fail so badly?

The market has failed to build enough homes because the system is broken. The Government benefits from the building of homes (GST, payroll taxes, and so on). But local government which controls much of it, receives little upside. And all the downside of “nimbyism”.

Councils’ planning focus seems dedicated to ring-fencing cities, trying to stop them from spreading. This implies density must increase, but New Zealanders are unused to apartment or other high-density living.

On top of this, poor economic management is rife. Over the past two decades, governments appear to have achieved significant GDP growth via migration. Yet compared to another developed country of similar population – Ireland – New Zealand has averaged net migration rates of more than 3x. Yet Ireland’s construction sector appears to be 3x larger.

Is there a solution?

There is little point highlighting a problem if you don’t have a solution. Those who abetted the problem will not be held to account. And for the (still) majority of people who own homes, some more than one, they have done well.

Capital gains tax (CGT) will not solve the problem. There is already limited CGT in the form of the bright-line test. Instead, CGT could risk the hoarding of housing as people avoid what amounts to a “tax when you sell”.

A deemed rate of return tax possibly makes more sense. Along the lines of what Susan St John of Auckland University has suggested. I would tweak the suggestion to focus on housing beyond primary residences and consider taxing that at a “fair dividend rate”. Perhaps 5% on the gross value.

This would sharpen investors’ minds on the real return of housing, while broadening the tax base to deal with the economic imbalance we face.

Yet, the levers of taxation may still not resolve the key underlying problem: More demand for homes, particularly in certain locations and of a certain type, than the country has or can produce.

One of the problems with the maligned KiwiBuild programme is that it focuses on building homes without correct analysis of the path to ownership.

Most people start off renting. It is not only the high cost of homes that has caused the crises, but the high cost of rent. If you want to scale homebuilding, you need to first scale home renting.

Charitable programmes such as that offered by Habitat for Humanity do exactly this. Habitat is addressing market failure with a “rent-to-buy” type model. Families pay affordable rents on their home. Then may have the opportunity to refinance and buy it once they are able to do so.

Only the Government can fix the system

We’ve looked at this from multiple angles. Tweak the tax. Remove the RMA. It might all help.

But it comes down to the disconnect between central and local government. It is central government that can ultimately lead large-scale infrastructure to facilitate development, while addressing skill shortages in building and trades.

The government did it post-World War II. Tens of thousands of homes were built across whole new suburbs. Skilled tradesmen were brought in or trained to build the new homes and even pre-cut houses from Austria were imported when local materials ran out.

This provided decades of affordable housing. Now it needs to start again with quality rental housing beyond the lumbering bureaucracy of the existing state housing system.

Renting in Europe

Vonovia is one the largest commercial providers of housing in Europe, owning more 400,000 dwellings across Germany, Sweden and Austria.

Typical medium-density Vonovia residences. Source: Vonovia

The company’s share price has doubled since 2015. It pays investors a yearly dividend of about 3%. It’s return on equity of about 14%, and compared to other businesses, was barely affected by Covid-19.

It is a resilient and defensive enterprise. Investors currently pay a 50% premium on tangible asset value to own this stock.

My point? Renting is an affordable option for people across Germany because of companies such as Vonovia.

New Zealand could benefit from a large-scale builder of affordable rental property. But it needs a commercial, market focus.

If the Government could kick-start such an operation, the company could then be floated on the starved NZX, allowing investors to buy a stake. It could be similar to the successfully managed float of power companies, which offered 49% of their shares to investors.

Investors in a housing scheme could then contribute to the building and rental of homes in a scaled and potentially profitable way.

While the private sector is also working on “build-to-rent” options, the impediments of central versus local government, the RMA, skill shortages and infrastructure deficits – it seems Wellington needs to spearhead things in a more ambitious way.

When thousands of medium-density dwellings offering affordable rents are rolled out, rents across the market could fall. This might encourage many marginal landlords to sell and invest in more productive areas – bringing more homes to the market and improving affordability.