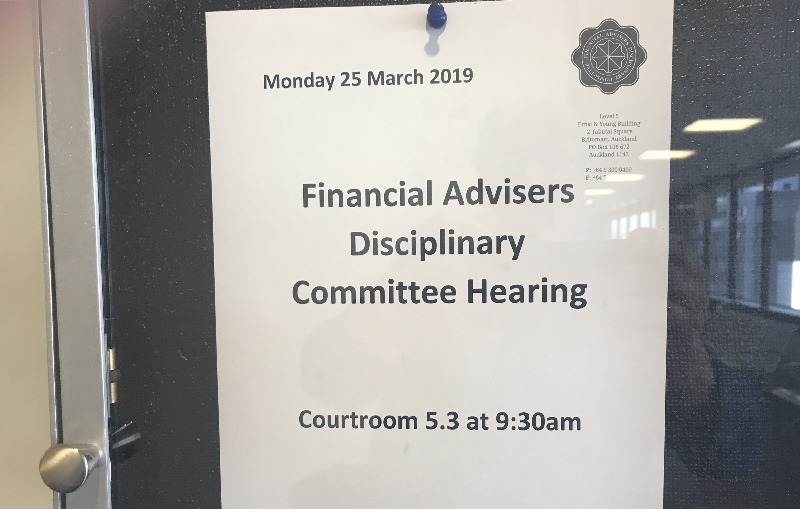

Sitting at the Auckland District Court on Monday, the FADC conducted a hearing into the case of an Auckland-based insurance adviser who is alleged to have failed to disclose pre-existing medical conditions on two client applications.

The case was bought by the Financial Markets Authority (FMA), but FADC chairman Bruce Robertson has suppressed the name of the adviser and the two clients until a decision on the matter is made.

The FMA’s counsel alleges the adviser breached Code Standard 8 by failing to ensure fulsome disclosure of his clients’ medical history and that this meant he did not provide good, personalised service to them as required under the Code.

While the case was of a “lesser order of seriousness”, it was one that has important consumer protection issues and is significant in the financial advice context, he told the hearing.

“Failure to ensure that fulsome disclosure is given is a common reason why insurance might be declined when claimed. So financial advisers must do their best to insure it occurs.

“Otherwise, a situation might arise where a policy is given that doesn’t meet requirements. And the consumer ends up paying for a policy that is useless.”

The FMA alleges that is what happened in one client’s case as the failure to disclose his medical history had serious consequences, with his policy ending up being cancelled.

This client, who was the first witness, originally bought a Sovereign policy through ASB then switched to a Partners Life policy on the advice of the adviser.

He alleges that, over the course of several “rushed” meetings with the adviser, the adviser didn’t ask him about his medical history at all and that, for this reason, he didn’t disclose a number of medical issues.

These issues included a back “ailment” which had been the subject of an exclusion in the Sovereign policy and which became the focus of much of the hearing.

The witness told the hearing he didn’t read the application in detail as he “had faith in his adviser” and only realised there was might be an issue with non-disclosure a couple of years later, in 2015, when he raised it with the adviser.

Under cross examination, the witness said that it was all about income protection and reducing his ACC cover so he didn’t see the need to discuss any pre-existing conditions himself. As such, he thought he had disclosed everything required.

The counsel for the adviser disputed the witness’s version of events. He said the adviser had worked through the 30-plus page application form in detail with the witness in several “relaxed” meetings, despite the witness’s claim he had no memory of this.

It was during this process that it emerged there was an exclusion in the witness’s Sovereign policy for a back “ailment” which the witness did not want to disclose in his Partners Life application, he said.

“The witness told my client there was no back ailment and that it was, essentially, a mis-statement on the earlier policy.”

His client took the witness at his word and, despite advising him of the significant risks that came with such non-disclosure, did not disclose the back ailment in the application.

The adviser said that it later emerged that the witness had not disclosed a number of other ongoing medical issues to him, or Partners Life. These were an arm injury which had required surgeries throughout his life and minor cardiac issues going back 10 years.

But it was the non-disclosure of the back ailment which became a focus of much of the hearing – as the FMA’s counsel argued that it constituted a breach of CS8. That’s because it was a failure to provide good personalised service, based on the information provided, to a client.

“An adviser is not giving good personalised service if they don’t properly address the risks of non-disclosure,” the FMA’s counsel said. “It was a fundamental error to take the witness’s word rather than looking at the other evidence, in particular the Sovereign exclusion, in detail.”

In response, the adviser’s counsel said the witness simply refused to disclose the back ailment to the insurer – despite the respondent’s advice. “There were no benefits for my client from not fully disclosing but how can you cope with someone who is not willing to tell the whole story?”

He also pointed the FADC to the Partners Life letter which cancelled the witness’s policy: it stated it was due to his extensive, non-declared medical history. “It was not just the back ailment which, on its own, would probably have been labelled a mis-statement and been given an exclusion in the policy.”

The second witness to give evidence against the adviser presented a more straight-forward case.

He said he started thinking about disclosure when he changed his policy from the Partners Life policy he got via the adviser to a new Asteron Life policy arranged by a new adviser. In his view, the contrast in approach was marked.

His meetings with the adviser were short and rushed and there was limited discussion of his medical history. “But when going through the process with Asteron Life there were more extensive questions about my medical history and I had to take a medical. That meant there was full disclosure.”

The adviser’s counsel said the reason for the difference in scope with the second witness was due to other reasons, including the witness’s new adviser’s desire to find a reason for the witness to change policies and generate a new commission.

Several expert witnesses also provided evidence for the FADC hearing.

One said that, although the landscape has changed following the code revamp in 2016, it would still have been good practice prior to that for an adviser to refer back to his clients’ medical history when providing advice.

Under the principles of the 2016 code advisers do have a wider remit and disclosure obligations have become far more important, he told the FADC in response to questions.

“But, even under the older code, I think the requirement would be for fulsome medical history disclosure because it is implicit under good practice.”

The other expert said he would expect that an adviser would have strongly recommended that the first witness’s back ailment be disclosed, especially given the Sovereign exclusion.

In a situation where the client refused to agree to disclosure of the issue, he would advise them to change their mind and advise them of the risks they are taking by not doing so, he said.

“I would make a file note about the refusal and probably advise the insurer, which would prompt closer examination by the insurer. There is a responsibility to not allow a mis-statement to be made to an insurer.

“Advisers need to take real care with disclosure. But if there is someone who won’t agree to disclose, there is not much you can do about it.”

The FADC hearing finished on Monday and the Council has reserved its decision till the “earliest possible opportunity”.